Darren Carty, Irish Grassland Association Council and Irish Farmers Journal

Over 100 farmers and industry delegates attended the Irish Grassland Association sheep conference and farm walk, sponsored by G€N€ IR€LAND and Mullinahone Co-op, in Aughrim, Co Wicklow, on Tuesday 26 April.

A focus running through the event was the importance of grassland management and its potential to underpin profitable enterprises. This was evident in all of the presentations at the morning conference and again in the afternoon on the farm of John Pringle which comprises a 50-cow suckler-to-beef herd and a flock of 250 mature ewes and 70 yearling hoggets with their lambs.

There is massive potential on Irish livestock farms to increase the volume of grass grown and utilised. This was the view of Micheál O’Leary, Teagasc Moorepark, in his presentation explaining PastureBase Ireland, Teagasc’s web-based grassland management tool, in operation since 2013.

Micheál showed that from drystock farms measuring regularly in 2015, there was a range in the volume of grass dry matter (DM) produced from 9.1t DM/ha to 14.7t DM/ha. Breaking up the year into three periods of spring (1 January to 10 April), summer (11 April to 10 August) and winter (11 August to 31 December), he also showed that grass growth varies greatly in spring with a range of 0.5t DM/ha to 1.7t DM/ha. This accounts for 8% of yearly growth in a typical year, with 61% in summer and 31% in autumn. While on the topic, Micheál described 2016 to date being far from the typical year, with grass growth running 40% behind previous years’ levels.

The drivers behind early spring grass growth were summarised into six areas as follows:

A lot of drystock and sheep farmers are not getting enough grazing out of their paddocks, according to Micheál.

“Large fields are not producing as stock are in there too long. This affects quality and liveweight gain and also limits the volume of grass grown (grazing regrowths). Looking at PastureBase, farms who achieved seven to eight grazings from paddocks grew 12 t DM/ha to 13 t DM/ha in these areas. There is also likely to be a nitrogen interaction but it shows what can be done compared to set stocking with two grazings per season only delivering about 5 t DM/ha to 6 t DM/ha. An extra grazing on dairy farms delivers 1,385 kg DM more grass. On sheep farms it could deliver up to 1 t DM/ha more worth in the region of €265/t.”

The importance of increasing the number of paddocks and operating a rotational grazing system was highlighted as a key take-home message. Applying sufficient nitrogen for the stocking rate on the farm is also another important consideration. However, Micheál cautioned farmers in this area.

“There is no point spreading 200 kg nitrogen over the year if your fertility is incorrect. 90% of soil samples are not at the optimum for soil fertility so the key is to start with lime and improve the pH”.

The final message delivered is that without measurement you cannot accurately identify how the farm is performing and where changes need to be made.

“I’d advise anyone interested in driving grass production to think about using PastureBase. It is free to farmers and is easy to access as long as you have access to a web connection.”

Welsh experience of rotational grazing large flock numbers

The concept of rotational grazing being possible no matter what type of enterprise or scale of enterprise is present was rubber-stamped by Welsh guest speaker Neil Perkins, who along with his wife Linda and family runs a flock of 2,500 ewes on Dinas Island in southwest Wales.

The farm extends to 600 acres (243ha), with two-thirds of this land classified as productive and the remainder a mixture of woodlands, coastal areas or rough grazing that contributes very little to the system.

Neil described the farm as having the potential for early grazing, but with shallow soils and exposed swards, the farm is at risk of burning off heavy covers in spring, if weather and wind direction and speed are unfavourable. At the same time there is a risk of burning up in a dry summer. Neil adds that the heavy clay nature of soil that is present limits the potential for grazing late in the year or out-wintering ewes.

The production system has therefore developed to exploit the farm’s resources of producing high quantities of dry matter during the main grazing season. Neil says there is as much emphasis placed on grass measuring and budgeting as there is on data recording in the sheep flock.

“We have focused on grassland for the last 10 years. We are now producing 30% more grass from the same area – that’s the same as having an extra 120 acres of land. It has come at a cost of £15,000 (€18,987) to set up the farm for rotational grazing but it is giving a return of £12,000 (€15,190) per year so it has more than paid for itself.”

This has been achieved in the main through close attention to soil fertility, reseeding with high-sugar grasses and mixed species such as red and white clover, plantain and chicory that have the potential for delivering high dry matter production and utilising rotational grazing to the maximum effect.

The rotational grazing system is interesting. Fields on the farm are laid out in 24- to 25-acre divisions and every field is run in its own rotational grazing system. This system is achieved by having one main fence which splits the field in half.

In spring, ewes and lambs are set stocked for a couple of weeks and as growth normally rises, each area is transformed into a rotational grazing system with six paddocks.

Square or rectangular fields are further divided into three parts in the same manner as spokes on the wheel of a bike with electric fencing, with animals tightened to one segment to begin rotational grazing.

“As soon as grass starts growing, we put ewes into one half. We then start subdividing which basically involves putting up 12 kilometres of electric fencing. Demand in each area is running on average at about 25 kg DM/ha per day. Once growth hits 44 kg to 45 kg DM/ha, we drop out one paddock and when we hit over 60 kg DM/ha we drop out another.”

Neil delivered a take-home message that is relevant no matter what enterprise is being run.

“You don’t have to go as technical as we did. If you can split a field in half and grow 10% more grass then the farm will be in a better position. This is the way we have gone and it’s only after we have achieved this that we move on and go to the next level”.

Exploring the potential of multispecies swards

Exciting provisional results on the potential of multispecies swards in sheep enterprises were presented by Dr Tommy Boland, School of Agriculture and Food Science, UCD. The results are from year one of a two-year trial which is funded by the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine and supported by collaborators through Smartgrass (researchers from UCD, Teagasc and AFBI), the project which aims to increase the yield and quality of forage/silage on livestock farms while also reducing any negative environmental impact of producing crops under intensive farming conditions.

The trial, which is managed day-to-day by PhD student Connie Grace, is comparing performance of mid-season lambs born in Lyons research Farm across four sward types. It started in August/September 2014 when the following sward types were sown;

Trial metrics

The swards were sown randomly across an area with five paddocks allocated to 30 twin suckling ewes and their lambs at a stocking rate of 12.5 ewes/ha. This was the entire area that was offered and with 2015 being a difficult year growth wise, concentrates were introduced to supplement any shortfall in nutritional intake when required. In total, there was 8kg fed/ewe to group grazing PRG, 19kg/ewe to PRG & white clover, 7kg/ewe to the six-species mix and 18kg/ewe to the nine-species mix group.

Extensive measurements were collected on ewe weight and body condition and lamb performance. Ewes were recorded at six week intervals while lamb performance (weighing) and faecal egg counts were carried out fortnightly. A drafting weight of 45kg live weight was set and after weaning lambs were grazed ahead of ewes in a leader-follower system to optimise performance with ewes used to graze paddocks from 5cm to 4cm.

Provisional results

Tommy presented results on all the areas described above. Ewe body condition score was highest six weeks after lambing on the nine species mix with very little difference between the others. This changed at weaning with the PRG & WC and six species mix best. The nine species mix regained top position however at breeding and housing with a BCS of about 3.2, slightly ahead of the other three groups. Ewe weight also varied throughout the year with ewes grazing the six and nine-species mixes heaviest from after lambing right through to housing.

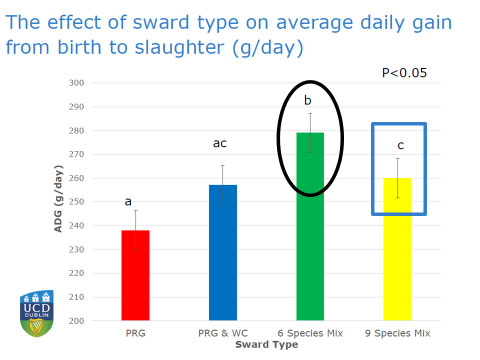

Moving onto lamb performance, Tommy showed a significant difference in weaning weight in 2015. Lambs grazing the six-species mix weighed 36kg at weaning with both the nine-species mix and PRG & WC swards weaning lambs at 34kg while lambs grazing PRG only swards were lightest at 32kg. As can be expected this was reflected in average daily live weight gain with lambs grazing six-species swards gaining slightly over 300g/day, significantly ahead of the PRG lambs gaining 285g.

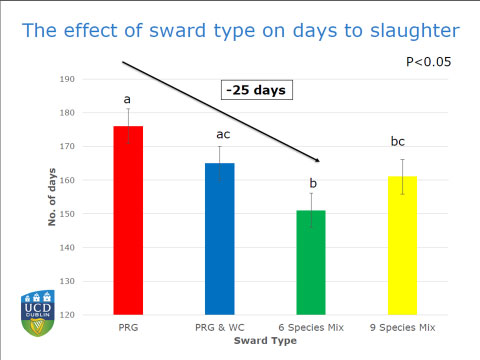

Figures 1 and 2 shows the effect of sward type on average daily gain from birth to slaughter and on days to slaughter. This visually shows the huge merit gained in year one of the trial from grazing multispecies swards. Lambs grazing the six species swards finished 25 days to slaughter earlier than those grazing PRG only swards.

Health impact

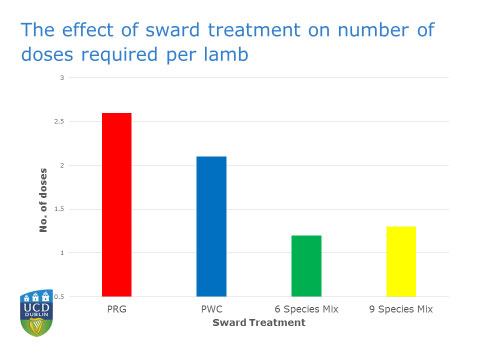

The lift in performance is stemming from higher performance attained from grazing a more diverse sward and also from a lower health challenge. The nine-species mix had the lowest faecal egg counts at ten weeks of age and longest period of time of over 70 days between the first and second anthelmintic treatment. This compared to about 50 days for the six species mix, 38 for the PRG & WC and 35 for lambs grazing PRG only. This had a significant impact on the number of doses required per lamb as shown in Figure 3.

Further research

Tommy stressed to farmers at the event that while the results achieved are very positive, they are only from year one of the study with further research required into areas such as persistency of swards, performance in varying soil types and rainfall levels, faecal egg counts and parasitic burdens, meat quality and amongst others animal interactions with the sward. For example, after one year the persistency of birdsfoot trefoil is questionable, especially given the high cost of seed. Further updates will be followed and more information can be got on the project at www.smartgrass.ie.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Witnessing the Pringle farm run a large number of animals in just three grazing groups showed what can be achieved at farm level and proves that rotational grazing systems can be set up to account for different flock/herd sizes and mixed grazing systems in a relatively low-cost manner.

John explains that the initial focus on the farm was to ensure field boundary fencing was adequate: “We started to improve grassland management many years ago and began working on boundary and internal fencing.

“We gradually split a few large 15 to 16 acre (6ha to 6.48ha) fields in two, with some consisting of new hedgerows and a double sheep wire permanent fence to improve shelter as we are pretty exposed. This worked well and I got used to seeing a high number of stock in fields of seven acres.

“Bob Sheriff, my Teagasc B&T adviser, and Pearse Kelly, who was a beef specialist at the time, visited to draw up a farm plan and recommended subdividing paddocks again. I thought there is not a hope of halving fields again with the numbers being run, but it works and proves itself.”

Cost was a major consideration in the move, as well as having the flexibility to remove fences if closing larger fields for silage. John explains how the temporary fencing works for him and how he gets sheep accustomed to electric fencing.

“Most of the ewes on the farm are now well used to electric fencing, so there is no problem there apart from one ewe who continues to test the patience, but could find herself on the culling list this year.

“I start the lambs with netted electric fencing, which works better to get them started. This type of fence works very well, but the higher cost [about €100 per 50m roll] wouldn’t be practical to roll it out across the whole farm.”

The fence is also slightly different to many similar types on the market, with vertical plastic sections providing more rigidity. The majority of temporary fencing used up to this year comprises PVC posts and polywire, which also works excellently for mixed grazing cattle and sheep.

“It doesn’t cost a lot to split a field in two. A roll of polywire will go a long way and with 20 PVC stakes [Picture 2], a field could be split for €70 to €100. I don’t have a mains fence, but the setup works fine with a normal battery fence and a car-battery fence. The only thing you have to really watch is that the sheep know faster than you when the battery is dead.”

John also wanted to make the system more labour efficient for a one-man operation and purchased a number of multi-strand electric gate systems. These worked out at a cost of about €26 each. They are attached with fittings to a timber stake with a self-contained post fastening the gate at the closing end.

Click on here to download booklet

|

|

We would like to thank our sponsors G€N€ IR€LAND and Mullinahone Co-op